The bones of the run-and-shoot offense were created in Middletown, Ohio in 1958 by longtime coach Glenn “Tiger” Ellison. The high school had a football team since 1911 and they never once had a losing season. But in 1958, that streak was on the brink. They were halfway through a 10 game season and found themselves sitting 0-4-1.

Ellison was an old school football coach. In his book Run and Shoot Football: Offense of the Future, he says motto was “Hit ‘em so hard and so often with so much that they simply cannot stand up in front of us!” They were a serious, ground-and-pound football team. In 1958 they were running “Woody Hayes’ Pulverising T”, but the results were less than ideal and it was taking its toll on the team. It wasn’t just the losing; it was what the losing was doing to the high school kids - and town - who had only known winning. The excitement was drained.

So, when Ellison created the proto-spread offense, it wasn’t because he was any kind of mad genius tirelessly working on a way to reinvent the game of football. No, he was simply a football coach who saw his kids no longer enjoying the game and wanted to find a way to inject some joy into it. On its face, it’s a simple conceit: how can I make a game fun again? Enter, the Lonesome Polecat formation.

It wasn’t called The Lonesome Polecat at first. Ellison doesn’t say what the original name was. It was Stan Lewis - the line coach - who suggested the name The Lonesome Polecat, “because it stinks.”

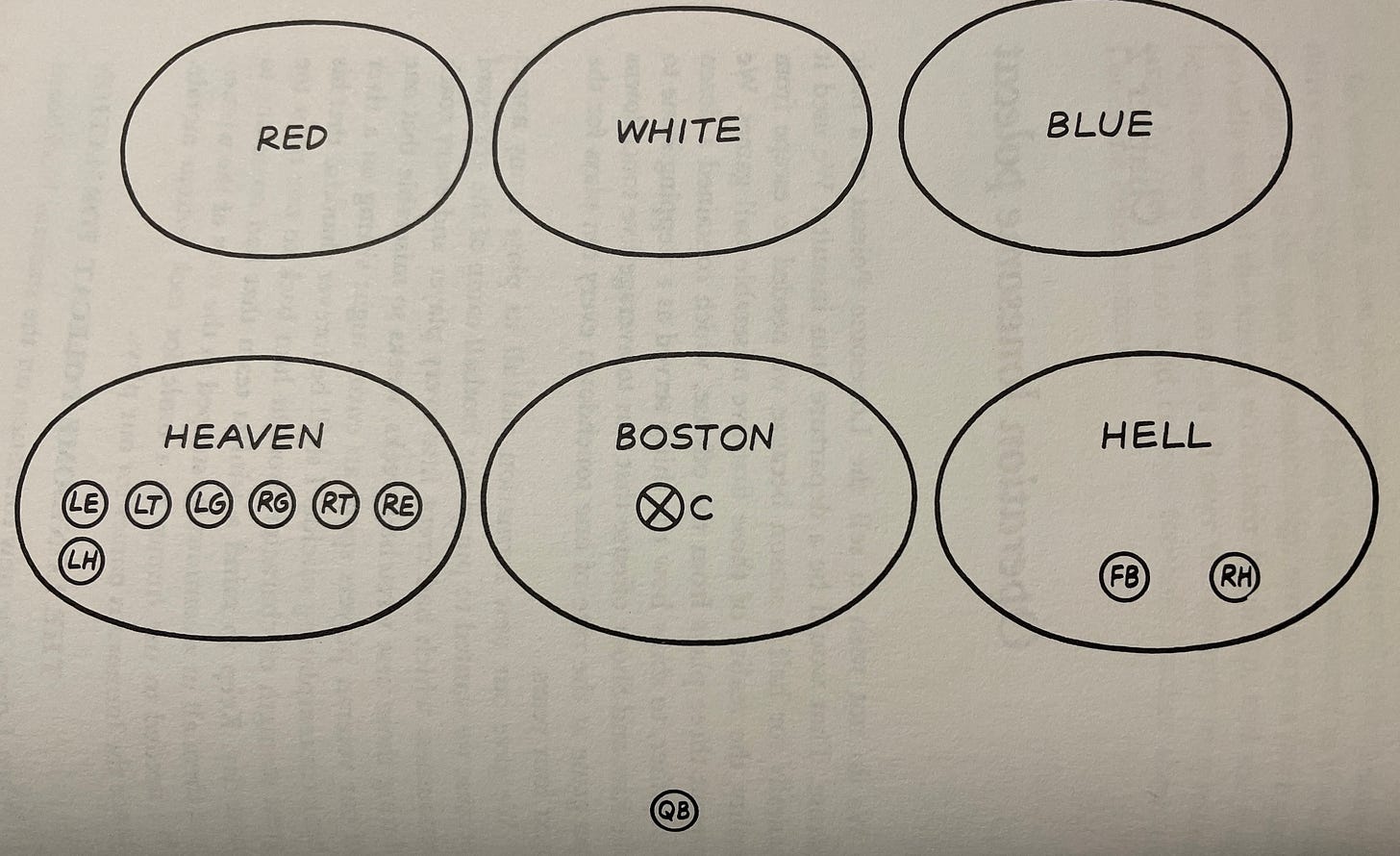

The name itself fit with the concept behind its creation. The zones you see above were also created in that spirit: “to purge our football camp of the graveyard seriousness which had crept into every player and every coach.” They may be talking about a route and say “Spring from Hell into the deep Blue.” To further follow the motif of having fun, the Polecat series was always run from no-huddle.

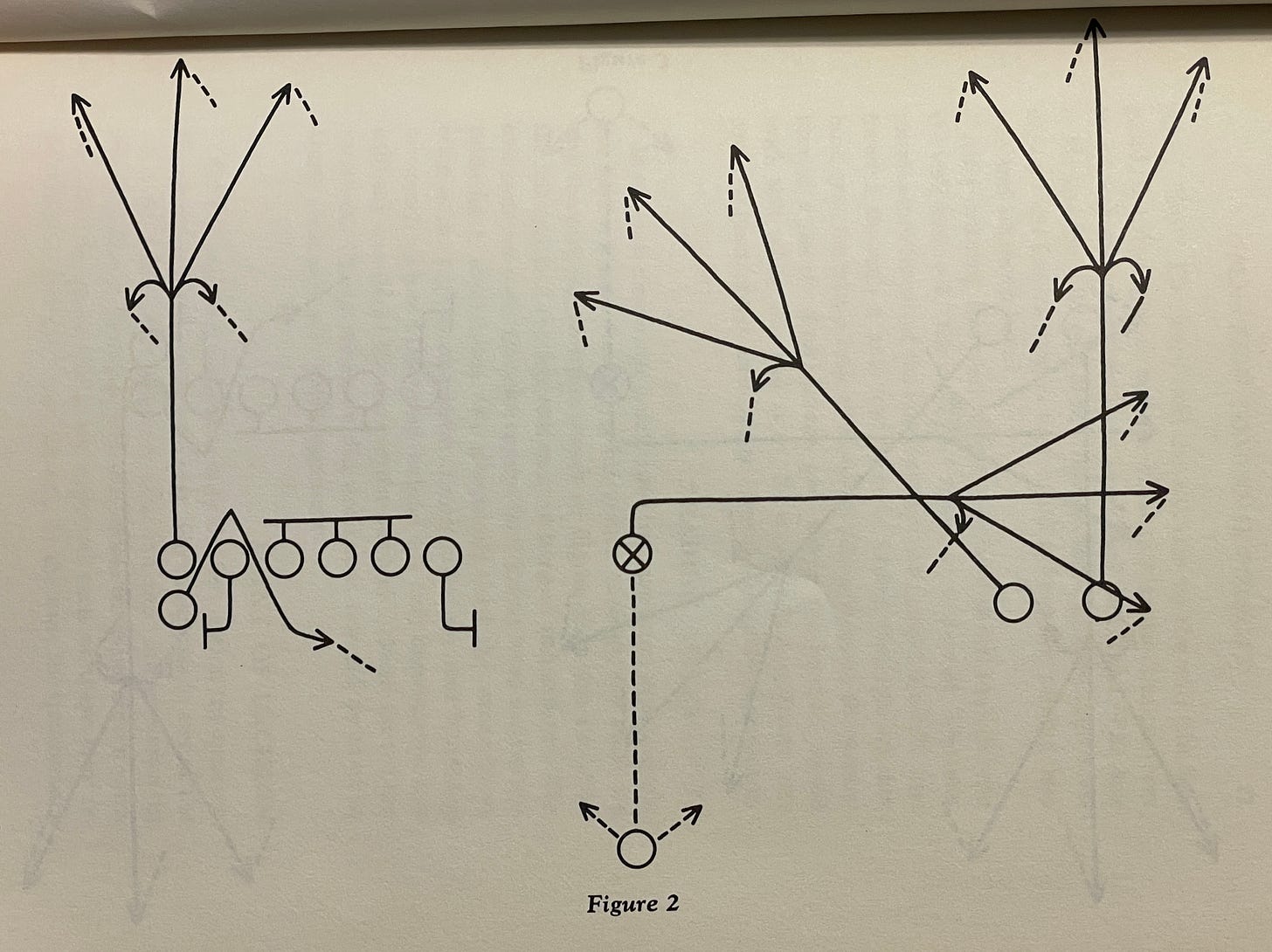

The first play they built was the Dead Polecat.

They’ve essentially got a tunnel screen on the left - which they could switch up to have the outside receiver to that side run if defenses started keying on it - and three routes to the left. The thing that jumps out are all the options. Depending on the position of a player, those routes can branch in any number of directions, and they can afford to do that because the receivers are so spaced out.

And then you get the QB moving and you’re really cooking with gas.

It was this last point that really served to push Ellison forward to the run and shoot offense. By giving the QB the opportunity to scramble and throw on the run, Ellison found that a passer could throw on the run just as well as he could from a set position. To take it even a step further, he believed that throwing on the run was more natural than throwing from a set position.

The Lonesome Polecat was never meant to be the core offense. Ellison himself says that installing this as the base offense would be “a departure into insanity.” But the run and shoot? Now that was sustainable, and something I suspect will look much more familiar than The Lonesome Polecat.

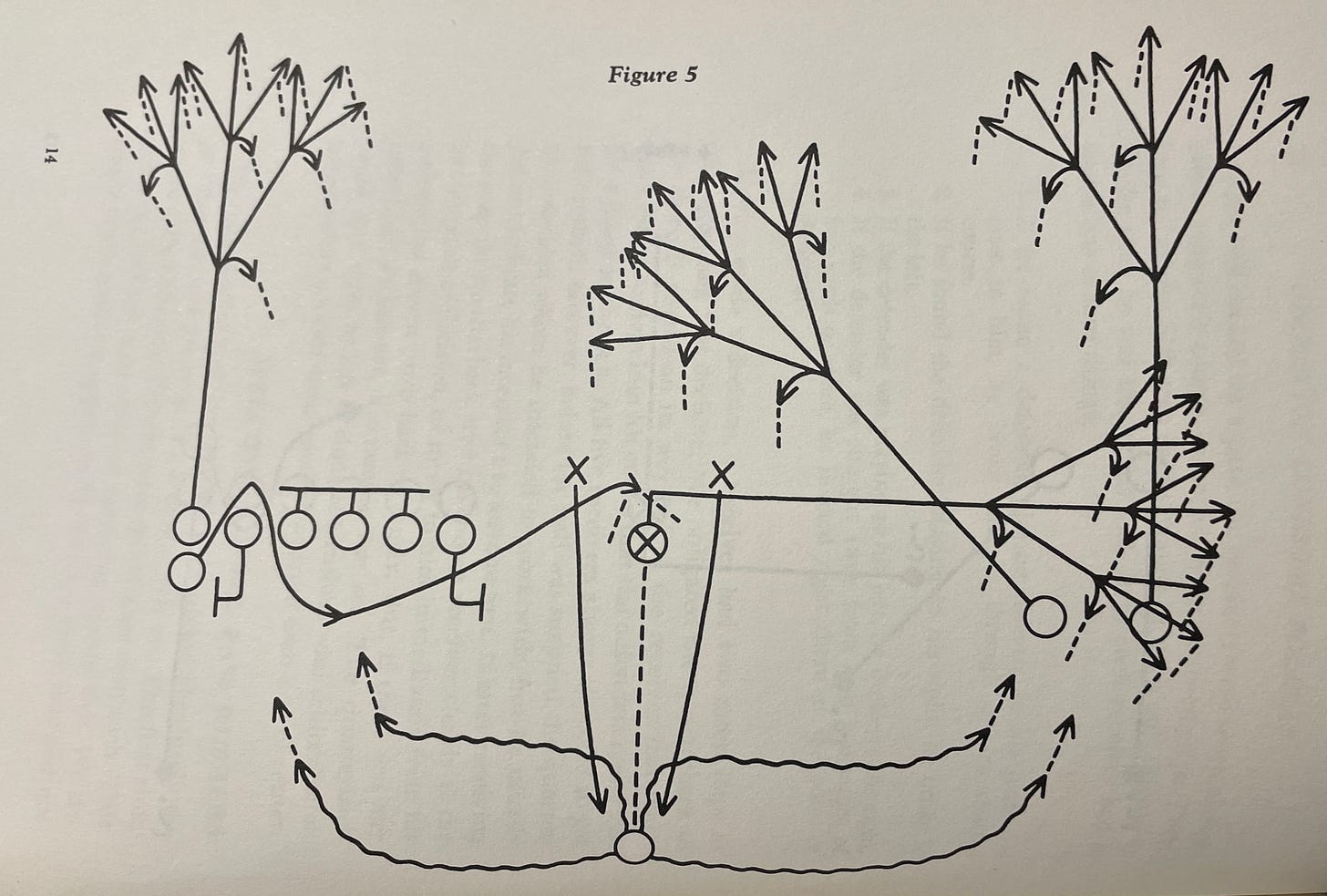

This was the base formation out of which every play was run: “a wide double-slot with the ends 17 yards from the ball but never closer than 6 yards to the sideline and with the interior linemen split 2 feet apart. The wingbacks were 1-3 yards from the tackles and 1 yard behind the line.”

In the early days of the run-and-shoot, defenses wouldn’t split their widest defender out to the widest receivers, driving Ellison to install something he called The Automatic Pass: something that could be seen as a precursor to the RPO.

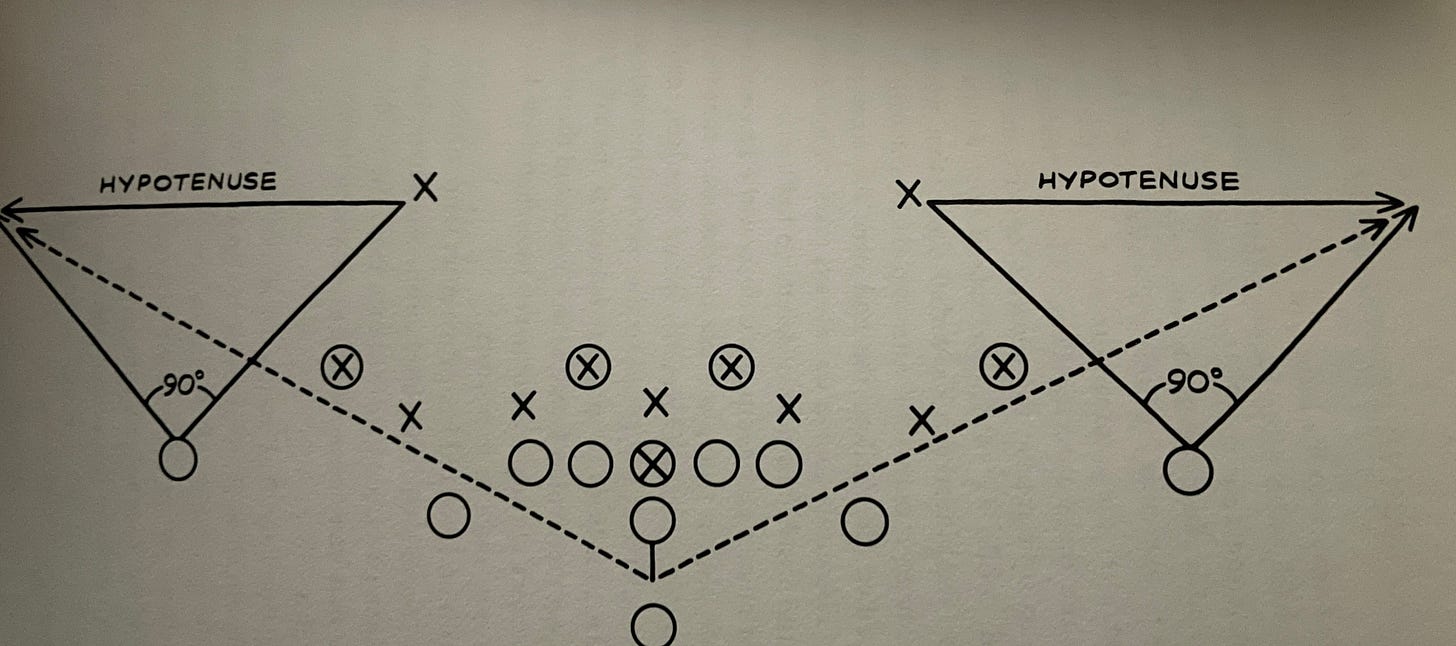

The signal was simple: if, after giving the signal to set, the receiver was still in a standing position and messing with his facemask, that told the quarterback to throw the automatic pass. He would tap the leg of the center, who would snap the ball. There would be no call, so no one else would move. The ball would be snapped, the quarterback would take a single step back and fire the ball at an angle that would make it impossible for the defender to make a play on. Ellison says that the automatic pass only had one pass deflection in 4 years.

It’s simple geometry, but geometry is how Sid Gillman built a legendary offense that still informs offenses in the modern NFL.

Ellison believed that great passers were made. “The man who sits dreaming of the day Santa Claus will come down the chimney and hand him a great passer ready-made may succeed someday, but his success will be accidental.” He was more concerned with a student in good standing who could move with at least “fair speed” and came eager to play. If he found that kid, the system would take care of the rest.

That’s a lot of information about Tiger Ellison and his run-and-shoot offense. So here’s a quick summary of Ellison and his system. The run-and-shoot offense featured some ideas that fit in perfectly with today’s game:

Completely no-huddle

Based out of spread formation, both for the purposes of creating room for passing and creating light boxes for running

Option routes to take advantage of post-snap defensive movement

“Now” throws depending on pre-snap coverage and defensive alignment, mirroring some RPO ideas

Aggressive on 4th down

Putting his backs in pre-snap motion

Having the blocking up front start exactly the same, making it difficult to determine if the offense was running or passing

Judging a QB more on intelligence and leadership than physical abilities

The original idea behind this post was to tie it in to Mouse Davis, The Air Raid and, ultimately, a play from the Packers win over the Cardinals, but let’s save that for tomorrow. For tonight, I hope you’ve enjoyed this primer on Tiger Ellison: a mad genius who really just wanted to make football fun again.